Microservices: shell commands with added flavor

Now in shiny new packaging with more network.

Wednesday, August 23, 2017

Click here to go to all posts. Also published on Hacker Noon

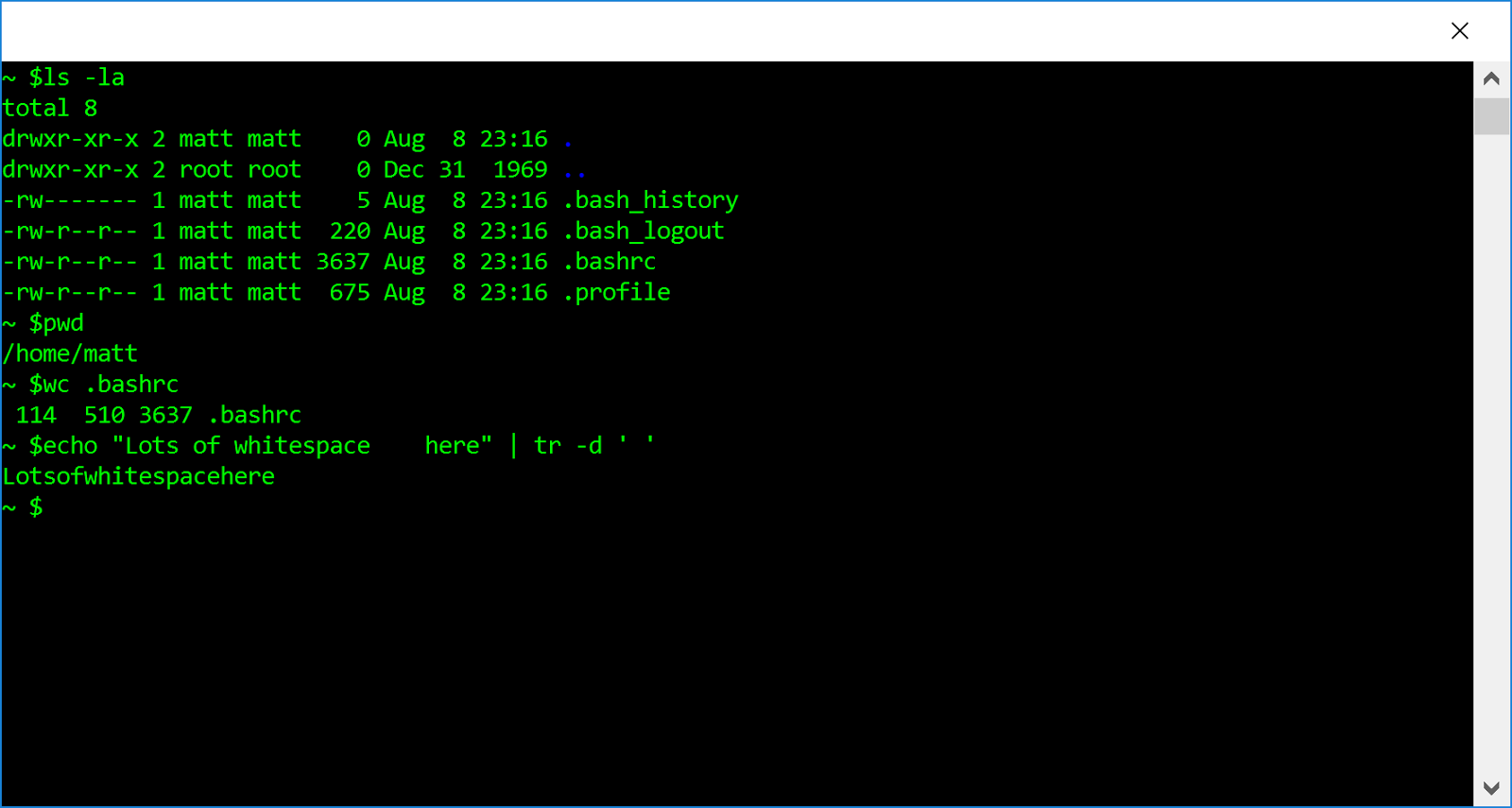

Shell commands are magic. To someone who doesn’t routinely use some form of shell interaction, watching someone work via shell is magical computerspeak. You can probably think of a scene in a popular movie with the classic hacker stereotype sitting there, typing away in something that looks like an alien language.

However, I spend quite a bit of time in the shell, and I know it’s not an alien language. Yet shell commands remain magical, just for a different reason.

I’ve looked at the code for some of them. I’m certain that tens of thousands of hours have gone into coding and battle testing each and every command. I know that some are baked into the shell I’m using, while many others are separate utilities stored somewhere in my path. Why are they magic?

It’s because they take the concept of “do one thing really, really well” to the extreme. I’m far more likely to doubt my own skills than I am to doubt the correct functioning of ls or tr or grep.

So how does this relate to microservices? I think this quote from *The art of writing Linux utilities by Peter Seebach sums it up nicely:

A good utility is one that does its job as well as possible. It has to play well with others; it has to be amenable to being combined with other utilities. A program that doesn’t combine with others isn’t a utility; it’s an application.

It turns out that microservices are, in many ways, shell commands made accessible over the longer distances. Sometimes it’s basic IPC. In many cases, it’s over the network.

This Linux.com article by Daniel P. Dern has a nice soundbite about this: “Microservices are one of the latest instances of the cosmic methodological swings of the cyberpendulum between ‘small, specific-task components’ (e.g., subroutines, Unix commands) and ‘massive monoliths.’”

So what does all this mean? There are several important ideas that apply to both microservices and shell commands. Let’s look at a few.

Do one thing well

This is central to both microservices and shell commands. Of course, this doesn’t mean it has to be limited to one use case. You want to build a certain amount of flexibility and coverage into your program, whether you’re expecting to be called over the network or via command line.

Are you trying to query system data, parse out key lines, format it, and save it to a file? Awesome, combine procps tools, grep, and sed. Do you have a complex application you’re trying to build? Good, write multiple microservices.

The idea here is to assemble your solution, not build it as a monolith.

Durability

This is where it gets a bit tricky. Shell commands aren’t expected to fail in the same way microservices are. However, the core concept here is durability.

For shell commands, the software is designed to handle edge cases, malformed data, resource issues, etc. And all the while, report back in an expected manner. Exit codes and error messages can be relied upon, even in failure modes.

For microservices, similar assumptions apply. Failure modes should be anticipated, and while that may mean a node going down, that too is anticipated and designed around.

Durability does not mean perfection. It means being able to withstand anything you throw at it.

Plan for use

There are a near limitless number of ways that shell commands can be combined. The entire foundation of shell scripts relies on the ability to mix and match commands in novel ways.

This applies to microservices as well: build a durable, predictable, sufficiently general microservice, and expect a flood of usage.

So what does this mean for the developer of the shell command or microservice? Some things you need to keep in mind:

- Aim for performance: no one wants to rely on a slow component

- Expect to be used as part of a larger whole: use standard data formats, easy flags/options, etc.

- Be transparent: whether it’s passing data on or returning a response, make it easy to understand what’s happening

These are just the start. You need to think from the perspective of someone looking for a tool that solves a specific problem. Will your shell command or microservice work? Will they **want **to use it?

Where to go from here?

There’s a lot of discussion around microservices, but that discussion misses the idea that we’ve been here before. The ubiquity of high-quality shell commands can serve as a guide to building high-quality microservices, as many of the same principles apply.

Shell commands are an essential part of an engineer’s workflow. Shouldn’t we expect the microservices to be just as durable, usable, and ready to assemble?

Next time you’re on a team talking about microservices, just remember: It’s a UNIX system! You know this!